Introduction Life Work Legacy Reflections Resources

The Work of Martin Chemnitz

Martin Chemnitz produced some 65 works, most of which were written over a relatively short, but industrious, period of time. Chemnitz had an incredible ability to deal with controversial topics with an approach that is both scholarly and winsome. Chemnitz rarely, if ever, reaches the heights of polemics for which Luther is (in)famous. Yet, his work reflects the extreme degree of familiarity Chemnitz had with the Bible, the church fathers, and Lutheran theologians.

Martin Chemnitz on the Council of Trent

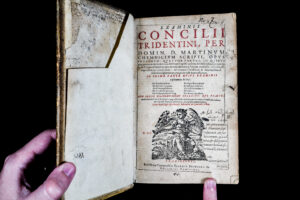

Main title page for this edition of Martin Chemnitz’s Examination of the Council of Trent. Martin Chemnitz. Examinis Concilii tridentini. Francofurti: Ex officina typographica J. Bringeri, 1615. OCLC # 9815608. CHI Call Number BX830 1545 .C413 1615.

The first of his major works was the five-volume Examination of the Council of Trent (1565–73). The Council of Trent was the Roman Catholic Church’s response to the questions posed by Luther and the Protestant Reformation. While the council addressed many problems, it solidified others to the level of doctrine. Additionally, Trent directly attacked many major tenants of the Lutheran faith, calling Lutherans heretics or worse. The Roman Catholic Church invoked the “consensus of the church fathers” in support of these claims, attempting to discredit the Lutheran church by placing it outside of this lineage.

Martin Chemnitz addresses the Council of Trent by investigating what the Bible, the church fathers, and other prominent Christian teachers have taught. Chemnitz shows that Trent’s claims are flawed and the Lutherans are more consistent with biblical and traditional Christian teaching. By a careful study of the history of the church, Chemnitz asserts the legitimacy of the Lutheran tradition. Not only that, Chemnitz also shows that scripture alone is a sufficient basis for doctrine, whereas tradition can and does err.

Chemnitz’s Examination is still a relevant document to Lutherans today. The nine years of labor Chemnitz poured into this four-volume work exude patient learning and dedication that worthy of praise and emulation. Further, the Council of Trent is still a binding document within the Roman Catholic Church. As a result, the doctrines Chemnitz tackles in this work are still taught by Rome, and his responses are still relevant. The Examination is not only a historically significant text, but it is also continues to shape Lutheran-Catholic relations.

Martin Chemnitz: Concord Co-Author

Before we can discuss the Formula of Concord and Book of Concord, we must first understand the historical context that led to the creation of these two documents. The mid- and late-sixteenth century was a time of massive unrest and even violence within the Lutheran church. The battles on fields and pages across Germany created an environment where the clear Concord statements were absolutely necessary for the Lutheran church to survive.

A Church Besieged

Following the deaths of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, the Lutheran church found itself steeped in controversy and division. Just four months after the death of Luther, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Pope Paul III moved quickly, planning to wage war on the Lutherans. When a papal decree made these plans public, Lutheran forces quickly moved to launch defensive action. Thus began the Schmalkaldic Wars. However, the Roman Catholic army was stronger. Lutheran cities and territories fell like dominos to the Emperor, but Charles wanted more than a military victory. In May 1548, Charles issued the Augsburg Interim, a series of orders meant to stifle Lutheranism in the occupied territories. Lutheran clergy were forbidden from teaching their Reformation beliefs, and the emperor was prepared to harshly punish any who disobeyed.

Lutherans across Germany looked to Philipp Melanchthon for guidance. Melanchthon, however, wished to avoid bloodshed and political strife above all. For this reason, Melanchthon authored the Leipzig Interim in late 1548. Melanchthon hoped to write an agreement that would allow Lutherans more freedom of conscience while still placating their Catholic occupiers. Instead, it merely further demoralized the Lutherans. Melanchthon treated a number of important issues as “adiaphora,” or indifferent. For example, the Leipzig Interim made room for both the Lutheran and the Roman Catholic understandings of justification. Rome excommunicated Luther for teaching that we are justified by faith without works. Melanchthon’s equivocation distressed those pastors and laypeople who had sacrificed dearly for their Lutheran confession of justification.

The Schmalkaldic Wars blessedly came to an end in 1553, though the final peace did not come until 1555. The Peace of Augsburg (1555) decreed that German territorial princes could decide the state church for their region. Cuius regio, eius religio: whose the region, his the religion.

Controversies Beget Confessions

Anti-Schmalkald double taler from 1546. The Holy Roman Empire’s imperial eagle is depicted breaking the “snare” of the Schmalkaldic League.

Although Lutheranism was a legal religion again, it was a deeply disunified one. Philipp Melanchthon’s involvement in negotiating the Leipzig Interim led many to view him as a traitor. But Melanchthon still had followers who sympathized with his conciliatory nature. The Wittenberg faculty included many professors who likewise departed from Martin Luther’s teachings. The Interims further blurred the lines between Lutheran and non-Lutheran doctrine. Additionally, the threat of more war and oppression from the Roman Catholics led some to desire increased unity with other Protestants, especially the Reformed.

Schismatic groups flourished. For example, a group beginning with John Agricola muddled the lines between Law and Gospel, some going so far as to reject the third use of the Law. The third use of the Law is when the Law functions as a guide in the Christian’s sanctified life. To reject the positive role of the Law is to be an Antinomian, “anti-Law,” and not a genuine Lutheran.

There was also a near-opposite error circulating. Matthias Flacius taught that original sin was the substance of fallen humanity. In this context, a “substance” is an integral part of a thing’s identity and nature; an “accident” is not. A dog is a substance, because the dog exists in its own right and possess a “dogness” that makes it a dog. The dog being brown and wearing a blue collar are accidents, because they do not affect the dog or its “dogness” essentially. Original sin, while not an accident, is also not the substance of humanity. Human beings are sinful, but they are not sin itself.

A plethora of other controversies also abounded. The pro-Reformed leanings of certain Wittenberg professors, often called “Crypto-Calvinists”, caused great disruption in the church. The role of good works and the human will in salvation also required a response.

The Formula of Concord

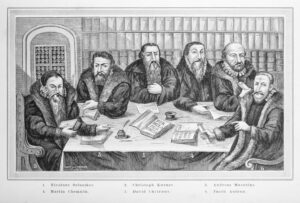

An engraved portrait of the authors of the Formula of Concord, labeled. From: Denkmal der dritten Jubelfeier der Concordienformel im Jahre des Heils 1877. St. Louis, Mo. : Zu haben bei M.C. Barthel, General-Agent der deutschen ev.-luth. Synode von Missouri, Ohio, u.a.St., 1877. OCLC: 39894126. CHI Call Number: STACKS BX8069.4 .D46 1877.

Chemnitz wrote the Formula of Concord (1577) with other Lutheran theologians in order to address this growing disunity and confusion. The Formula of Concord sought to give clear, scriptural responses to each of these controversies and more. However, it did so while shying away from polemics. Very few divisive individuals are actually named in the Formula. This avoided unnecessary conflict while still addressing the doctrinal problems pressing on the church.

The Formula of Concord underwent many drafts. It began as a series of sermons given by Jacob Andreae in 1573. He developed the concept further together with Martin Chemnitz, David Chytraeus, Andrew Musculus, Christopher Cornerus, and Nicholas Selnecker. Among these men, Chemnitz was especially significant. Chemnitz heavily revised Andreae’s earlier work, and worked to combine this with a similar document drawn up by Lutheran theologians from southern Germany. The result was a draft of the Formula known as the Torgau Book. They circulated this document throughout the Lutheran territories, in order to solicit comments and revisions. Taking the reviewers’ suggestions into account, the six men finally signed the Formula of Concord on May 28, 1577.

Martin Chemnitz and the Concord Consensus

During the three years between the completion of the Formula of Concord and the publication of the Book of Concord, Chemnitz and his colleagues worked tirelessly to persuade as many laypeople, pastors, and theologians to sign the Formula of Concord. This was, at times, a challenge. For example, Tilemann Heshusius was a stalwart “Gnesio-Lutheran” (“true Lutheran”) who was deeply concerned by the Crypto-Calvinists and other false teachers within the Lutheran church. However, he refused to sign the Formula because it did not explicitly name the false teachers condemned by its articles.

However, this diplomacy was intentional and ultimately successful. Naming the men who taught these falsehoods would include, among others, Philipp Melanchthon. Despite his many failings, Melanchthon was a beloved teacher—he had mentored Martin Chemnitz himself!—who had contributed much to the Lutheran church. It was enough to condemn the teachings, if not the man, in order to avoid additional strife and confusion. This was a particular gift of Martin Chemnitz: by avoiding polemic and additional anger, he could address these highly fraught topics in a way that finally established a unified and systematic

The Book of Concord

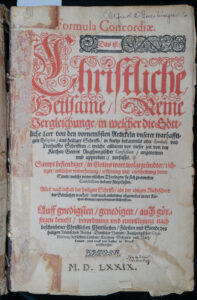

Cover of a 1579 edition of the Book of Concord, from the Concordia Historical Institute rare books collection. This edition is interesting because it appears to be a pre-print run or draft edition of the Book of Concord, and is, as such, incredibly rare and unusual. This piece is not currently listed in our online catalog, but it is used on our behind-the-scenes archives tours and is available to on-site researchers by request.

The editors of The Book of Concord (1580) intended it as a way to bring a definitive end to these controversies—and address future ones. The Book of Concord brought together the Formula of Concord with many writings of Luther and Melanchthon—the Small and Large Catechisms, The Augsburg Confession and its Apology, The Smalcald Articles, and On the Power and Primacy of the Pope—and the three ecumenical creeds—The Apostles, Nicene, and Athanasian creeds. Taken together, these documents consist of the rule and norm of Lutheran doctrine and practice into one coherent, mutually agreed upon document.

Published on June 25, 1580, the fifty year anniversary of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession, the Book of Concord is one of the most significant works for the Lutheran church. The editor of the reader’s edition of the Book of Concord writes the following:

June 25, 1580, therefore, is as important a day for Lutherans as is October 31, 1517, the date Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses. As a result of the hard work of Chemnitz and others, over eight thousand lay people, pastors, and theologians had signed their names to the Book of Concord. Throughout Germany, and eventually in lands through the world, the Book of Concord united people around the true teachings of God’s Holy Word. (“Introduction to the Formula of Concord,” in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. A Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord, William Hermann Theodore Dau and Gerhard Friedrich Bente, trans, Paul T. McCain et al., ed [St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005], 488.)

Chemnitz, Andreae, and their co-editors hoped to provide the church with an unchanging, exhaustive confession of what the Bible teaches. As we will discuss in the “Legacy” section, this has proven to be the case. The Book of Concord provided a stable statement of faith from which the Lutheran church was able to spread, grow, and thrive.

On the Two Natures of Christ

Title page from a 1578 edition of Chemnitz’s De Duabus Naturis in Christo.

In between these hugely important works, Chemnitz also published On the Two Natures of Christ (1578), a wildly influential work on the communication of attributes and the relationship between Christ’s humanity and divinity.

The Crypto-Calvinist Controversy of the 1570s was, in part, a result of division over the person and natures of Christ. The Reformed did not believe that Jesus was physically present in the Lord’s Supper, because His body was in heaven because of Jesus’s Ascension. Jesus’s body, the Calvinists argued, was a circumscribable human body, one that could not be in two, let alone manifold, places at once, namely, in heaven and on the altars of churches around the world.

John Calvin, in his Institutes on the Christian Religion, argued that Jesus can only change matter around Him rather than defy the laws of physics in His own body. For example, Jesus can command water to support Him when He walked on water, and He can command the stone of His grave or the stones in the locked upper room to yield or move and then return to their original place. To put it more crassly, Calvin claims that Jesus can perform telekinesis, but He cannot teleport.

While this is not in line with Luther’s thinking, this idea crept into the Lutheran church, especially during the 1570s. Martin Chemnitz sought to address it directly in this work, outlining a confessional Lutheran understanding of Jesus’s person and natures. Chemnitz argued from scripture and the church fathers that Christians have always believe that Jesus’s divine nature exalts and enables His human nature to do divine, supernatural things, especially after the resurrection. This is how Jesus is able to perform miracles, walk through solid stone walls, and—perhaps most importantly—be present in His Supper for us.

Martin Chemnitz’s Life’s Work: The Loci Theologici

Title page from: Martin Chemnitz. Loci Theologici. Polycarp Leyser, ed. Francofurti & Wittebergae : Sumptibus Christiani Heinrici Schumacheri: Typis Balthasaris Christoph. Wustii, 1690. OCLC: 26407315. CHI Call number: RARE FOLIO BT27 .C511 1690.

Chemnitz’s life’s work was his Loci Theologici (1591), derived from his lectures on Melanchthon’s Loci Communes and, though never fully completed, published posthumously by the printer and editor Polycarp Leyser. The scope of this work is highly exhaustive. God, the Trinity, the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit, Creation, angels, sin, the human will, the Law, the Gospel, revenge, poverty, chastity, justification, good works, the church, the sacraments, and marriage are all treated in this encyclopedic work. It is so long, in fact, that significant portions of it are still not available in English!

Chemnitz’s Loci Theologici is perhaps the closest thing in the Lutheran tradition to Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica. Like the Summa, this work is intended for students, as it originated as university lectures. It continues to be a helpful resource to Christians of all ages, as Chemnitz’s thorough approach and depth of theological knowledge continue to illuminate minds even today.

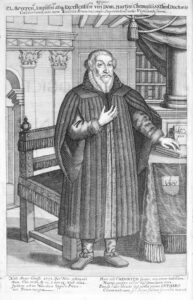

An engraved portrait of Martin Chemnitz. From: Martin Chemnitz. Loci Theologici. Polycarp Leyser, ed. Francofurti & Wittebergae: Sumptibus haeredum D. Tobiae Mevii, & Elerdi Schumacheri, anno 1653. CHI call no.: Rare books, Folio BT70 .C54 1653.

The Prolific Pen of Martin Chemnitz

This list is far from an exhaustive catalogue of the works Chemnitz produced during his life—much of his work is less well-known, very rare, or even lost, unfortunately. There is a great deal of work to be done by scholars and translators of the Reformation and Lutheranism. Thankfully, however, Martin Chemnitz is more accessible than ever because of recent technological and scholarly developments.

The online Post-Reformation Digital Library (PRDL) provides access to digital copies of some 207 titles and 265 volumes of Martin Chemnitz, at the time of writing. As we discuss in the “Legacy” section of this exhibit, more Chemnitz is available in more languages than ever before seen in history.

Sources

John Calvin. “Of the Lord’s Supper, and the Benefits Conferred by it.” Institutes on the Christian Religion. Book IV, Chapter 17. Trans. Henry Beveridge. 1845. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Web. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.vi.xviii.html.

“Controversies and the Formula of Concord.” In Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. A Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord. William Hermann Theodore Dau and Gerhard Friedrich Bente, trans. Paul T. McCain et al., ed. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005.

“Introduction to the Formula of Concord.” In Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. A Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord. William Hermann Theodore Dau and Gerhard Friedrich Bente, trans. Paul T. McCain et al., ed. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005.

“Martin Chemnitz (1522–1586).” Post-Reformation Digital Library. Accessed September 28, 2022. Web. https://www.prdl.org/author_view.php?a_id=544.

Quentin D. Stewart. Lutheran Patristic Catholicity: The Vincentian Canon and the Consensus Patrum in Lutheran Orthodoxy. Zürich: LIT Verlag, 2015.

Georg Williams. “The Works of Martin Chemnitz: A Bibliography of Titles, Editions, and Printings.” Concordia Theological Quarterly, vol. 42, num. 2 (April 1978). 103–114. Web. Accessed September 28, 2022. http://www.ctsfw.net/media/pdfs/williamsworksofchemnitz.pdf.