Introduction Life Work Legacy Reflections Resources

The Legacy of Martin Chemnitz

Martin Chemnitz has remained a relevant theologian within the Lutheran church as it has grown and spread over time. The collections at Concordia Historical Institute allow us to trace Chemnitz’s importance in North American as well as global Lutheranism.

Martin Chemnitz and the Development of the Lutheran Church

The Book of Concord

The importance of the Book of Concord in the development and solidification of the Lutheran church cannot be overstated. Historians of the Reformation look at the second half of the sixteenth century and beginning of the seventeenth century as a period of “confession-building” or “confessionalization,” during which time both the Catholic and protestant churches sought to systematize and enforce the theological changes wrought by the Reformation. For the Roman Catholic Church, this was achieved most directly in the Council of Trent. For the Lutheran church, the Book of Concord served to unite and systematize Lutheran doctrine into one authoritative volume, which could then be used to maintain good order and right teaching within its churches.

The Book of Concord has served as a doctrinally normative document within the global Lutheran community for nearly 450 years. Theologically conservative Lutheran bodies continue to require pastoral candidates subscribe unconditionally to the Book of Concord in order to be eligible for ordination. This includes members of the International Lutheran Council, such as the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, The Lutheran Church—Canada, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Brazil, and the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church, Germany. As a result, Concordia Historical Institute holds a number of historical and contemporary editions of the Book of Concord. In fact, many of the major players in the Saxon migration that led to the inception of the Missouri Synod, including C.F.W. Walther, Wilhelm Loehe, and F.C.D. Wyneken, were instrumental in renewing interest into the Book of Concord and its authors.

Martin Chemnitz’s Other Works

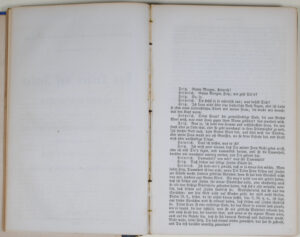

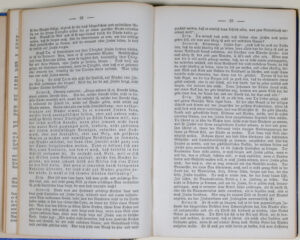

Martin Chemnitz played a role in scholarly and lay resources alike in the early Missouri Synod. Below is a nineteenth century work on lending that includes sections from Chemnitz. Chemnitz and Luther selections are re-worked into this winsome dialog between friends discussing issues of money, lending, and Christian giving.

- “Lending and Interest on the Basis of Holy Scripture.” Das Leihen auf Zinsen auf Grund der heiligen Schrift : und nach den Zeugnissen der ältesten und berühmtesten Kirchenlehrer, namentlich nach den Zeugnissen von Martin Luther und Martin Chemnitz, zur Lehre und Warnung für das Christliche Volk beleuchtet.

- First page. You can see how the text is written in dialog, almost like a play.

- A reference to Chemnitz appears on the left-hand page.

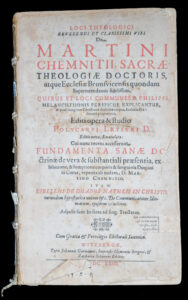

CHI has a number of Chemnitz’s works that were owned by significant persons and show significant use. For example, former Concordia St. Louis Seminary presidents Franz Pieper (1852–1931), Ludwig E. Fuerbringer (1864–1947), and Alfred O. Fuerbringer (1903–1997) all owned sixteenth and seventeenth-century editions of works by Chemnitz and his colleagues.

- A copy of the Loci Theologici owned by John Theodore Mueller. Mueller authored Christian Dogmatics (CPH 1968), a paraphrase of Francis Pieper’s German Christliche Dogmatik (CPH, 1917-24).

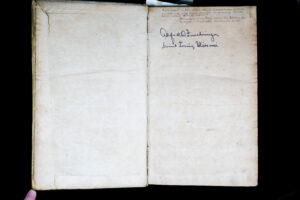

- Alfred O. Fuerbringer’s signature in a copy of Chemnitz’s Loci Theologici. Dr. A.O. Fuerbringer was president of Concordia Seminary from 1953–1969. Dr. Fuerbringer would eventually leave with the Walkout in 1974 and join Seminex.

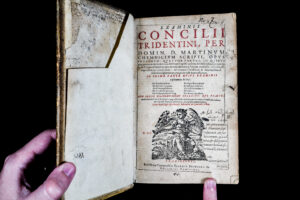

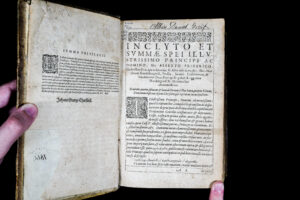

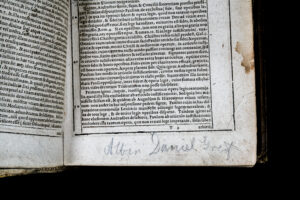

Pastors and seminarians also utilized these texts: editions of the Book of Concord as well as Chemnitz’s Examination of the Council of Trent bear the signature and notes of Albin Daniel Greif (1849—1914), who emigrated from Thuringia in 1868, graduated from Concordia Seminary in St. Louis in 1870, and was ordained by C.F.W. Walther that same year.[1]

Gallery: Albin Daniel Greif Reads Martin Chemnitz

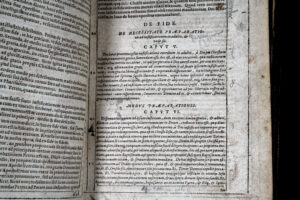

- Main title page for this edition of Martin Chemnitz’s Examination of the Council of Trent. Martin Chemnitz. Examinis Concilii tridentini. Francofurti: Ex officina typographica J. Bringeri, 1615. OCLC # 9815608. CHI Call Number BX830 1545 .C413 1615.

- Title of an introduction. Note the signature from Albin Daniel Greif at the top of the page.

- Another signature, perhaps from when Grief was a younger man.

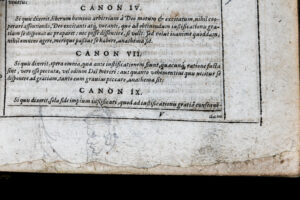

- Can you spot the little face in the second heading?

- Another face in profile, presumably drawn by A.D. Greif.

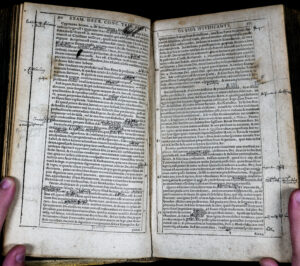

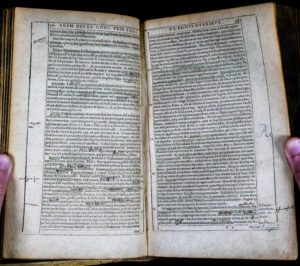

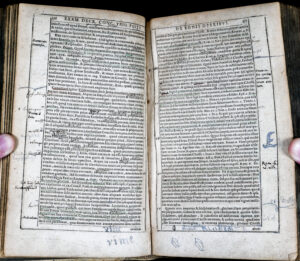

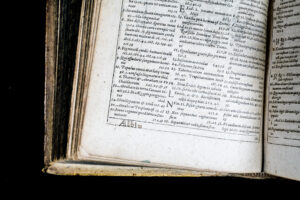

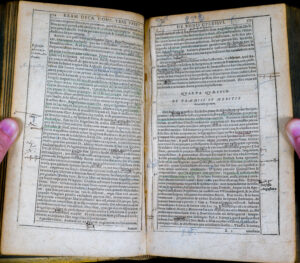

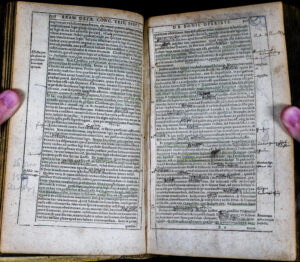

- This copy of Chemnitz’s Examen shows significant annotation in some sections, as though it were perhaps read for a class.

- Heavy annotation with a stray doodle

- Doodling intensifies.

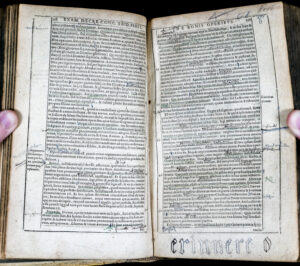

- Greif (presumably) has written “erinnere” or “remember” in a whimsical gothic script at the bottom of this page. Perhaps part of this was going to be on a test?

- “Ora”—pray—and “Tridentium”—of Trent—appear, again in a fanciful script. Greif seems to have enjoyed making his own “word art”!

- Just in case it wasn’t absolutely clear who was reading this work of Chemnitz…

- A stray date—November 26 1869—suggests that it is likely that this was a book used by Albin during his time at seminary.

- A stray date—November 26 1869—suggests that it is likely that this was a book used by Albin during his time at seminary.

“Reading” A.D. Greif

At first glance, you may see something like this and be shocked. You may think to yourself, “What a shame that someone wrote all over this old book!” However, this is actually a very good and useful artifact for us to have. In fact, marginalia like this can show us a lot about how people in the past read and utilized these books.

For example, A.D. Grief would have been at Concordia Seminary during the date written in this book. Therefore, it is not unlikely that he was reading this as part of the curriculum at the seminary. And, in order to have had the time it would take to make all these doodles, they must have spent a decently long period of time on it. The differentiation of the signatures also suggests that Greif held onto this book and continued to use it in the rest of his career. Additionally, because of the age of the edition (1576) and evidence of previous use (other signatures, marginalia in other hands), it is likely that this book was used by generations. Perhaps it was a family heirloom or something he brought with him from Germany when he moved to America, for example.

After serving in congregations across the country, Albin Daniel Greif eventually became the president of the Iowa District. He had a full career, and his adopted son, Herman Peter, also became a Missouri Synod pastor. With this in mind, how many lives did this work of Chemnitz touch through the ministry and legacy of Rev. A.D. Greif?

Martin Chemnitz in America

Early English Translations

While the individual works within the Book of Concord were available in English, the volume itself, as well as Chemnitz’s other works, were not available in English for a very long time. But the move to America and the new need for English-language evangelism and catechesis—as well as the eventual, but sudden, abandonment of German as the language of the church as a result of World War I—resulted in the long-awaited entry of Chemnitz into the English language.

Ambrose and Socrates Henkel published the first full English translation of the Book of Concord in 1851 with a second revised edition appearing in 1854. The Henkels relied on the German text, whereas the 1921 (and more well-known) Concordia Triglotta, the third English translation of the Book of Concord, incorporated both the Latin and German texts, with the inclusion of variant readings within square brackets.

Martin Chemnitz in Contemporary English Translation

When the German critical edition, the Bekenntnisschriften, appeared in 1930, there was interest in creating a similar volume in English. However, this has never materialized. Of modern significance is the Kolb-Wengert Book of Concord (Fortress Press, 2000), a new translation completed by scholars from both the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. Additionally, the Reader’s Edition (Concordia Publishing House, 2004; rev. ed. 2006), a revision of Bente’s English translation from the Triglotta, further helped popularize the Book of Concord among laypeople.

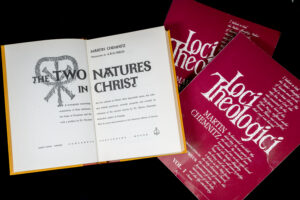

Chemnitz’s stand-alone work has also been of increased interest in North American and global Lutheranism in the past fifty years. The Committee for Scholarly Research, a group for furthering Lutheran scholarly endeavours, made plans to begin a Chemnitz translation project in 1960. However, the exact fate of this project is uncertain. Concordia Historical Institute holds one of the working copies of this project from Concordia Bronxville (then Concordia Collegiate Institute) professor and registrar Rev. Henry E. Proehl (1898–1964).[2] However, it is unclear what happened to the remaining translator’s projects.

- Cover. Martin Chemnitz. Examen Decretorum Concilii Tridentini: Fourth Part, Third Topic. Henry Proehl, trans. Unpublished, 1961.

- On the inside, it is clear that this is a working copy, as there are pen corrections to the typed manuscript.

Martin Chemnitz and the Concordia Seminary St. Louis Walk Out

The first full translation of a major work by Chemnitz into English was The Two Natures in Christ, translated by J. A. O. Preus II and published in 1971 through Concordia Publishing House. Preus is perhaps most famous as his role in the 1974 Concordia Seminary St. Louis Walk Out and the circumstances surrounding it. On February 19, 1974, the majority of the faculty and student body of Concordia Seminary dramatically left campus to start their own Seminary in Exile (“Seminex”) in response to tensions between the seminary and the LCMS over doctrinal concerns.

Reflecting on his own controversy-fraught career during a lecture at Concordia Seminary in 1986, Preus, remarking on how he was able to “have some sanity left,” said,

“I credit it partly to the good Lord and partly to the fact that I was able to spend an hour every day of my life with a very wise, bright, sound, orthodox, biblical, confessional Lutheran by the name of Martin Chemnitz.”[3]

Losing (and Finding) Martin Chemnitz

Also of note was Rev. D. Georg Williams (1950–2021), an LCMS pastor and Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort. Wayne graduate and adjunct professor. Until recently, Chemnitz’s treatise on the Lord’s Prayer was virtually unknown. The original Latin edition was unfortunately lost. But, the text survives in an exceedingly rare 1598 English edition published by John Legate. When Rev. Williams updated and published a revised text, he brought a remarkable meditation on the Lord’s Prayer into the light of day.[4]

The Global Martin Chemnitz

As Lutheranism has grown into a global faith, so also has Chemnitz’s theological legacy. Amazingly, Martin Chemnitz’s work has been translated into two dozen languages, including Latvian, Russian, Chinese, Ukrainian, Korean, Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Tswana, Malagasy, Sinhalese, Swahili, Kyrgyz, Amharic, Tamil, Turkish, Yala, Khmer, Czech, Telugu, Cebauno, Lithuanian, and even German, as much of Chemnitz’s work was written in Latin![5]

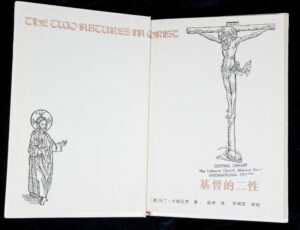

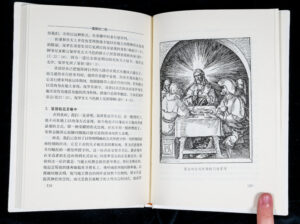

- [Two Natures in Christ. Chinese.] Nan jing : Yi lin chu ban she, 1996. OCLC: 300237166. CHI Call Number: STACKS BT200 .C43126 1996.

- This Chinese translation of Chemnitz’s Two Natures in Christ features stunning Albrecht Dürer woodcut illustrations.

- [Examen Concili Tridentini. Russian.] uncanville, USA : World Wide Printing ; Macomb, Mich. : Lutheran Heritage Foundation, 2005. OCLC: 844767250. CHI CAll Number: STACKS BX830 1545 .C517 2005.

Martin Chemnitz: “prince of the theologians”

Even if it is a cliché—and perhaps a slightly ahistorical one—it’s still true: without Martin Chemnitz, who knows what would have become of the memory and legacy of Martin Luther. Chemnitz systematized what it meant to be Lutheran in a way that allowed the Lutheran church to spread all around the globe in the 500 years since Luther began the Reformation while still retaining its doctrinal “shape.”

The theologian and church historian Heinrich Schmid wrote the following sketch of Chemnitz:

Gerhard frequently refers to [Martin Chemnitz] as “the incomparable theologian;” Quenstedt styles him, “without doubt the prince of the theologians of the Augsburg Confession;” and Buddeus, “that great theologian of our Church, whom no one will refuse to assign the chief place after Luther among the defenders of the Gospel truth… His De Duabus Naturis (1570) has been repeatedly called “an epoch-making production” (Kahnis, Luthardt), while his two treatises on the Lord’s Supper, De Coena Domini (1560) and Fundamenta Sanae Doctrinae, are especially valuable for their thorough discussion of Scripture, and their historical development of the subject. The Examen Concilii Tridentini (1565-73) is the ablest defence of Protestantism ever published…Wealth of Scriptural learning, profoundness of reasoning, clearness and accuracy of statement, well-balanced judgment, simplicity and freshness of style, a constantly practical tendency, and devout feeling, are the prominent characteristics of his works.[6]

This warm praise is appropriate for Chemnitz. Chemnitz’s work as a churchman and theologian have had and continue to have a huge effect on Lutheranism globally. From the Book of Concord to his Examination, Chemnitz answered questions that we continue to ask today. His answers have proven to be faithful, helpful, true, and enduring.

As the church faces an ever-changing world and ever-challenging contexts, it is helpful to return to our fathers in the faith. Martin Chemnitz confronted many of the same problems we struggle with today in our church and in our society. The legacy of Martin Chemnitz continues to inform our Lutheran churches around the world, and will continue to do so until Christ returns.

Next Page

Notes

[1] “GREIF Albin Daniel,” Genealogie Herrmann, accessed 6 October 2022, web, https://genealogie-herrmann.de/genealogy/getperson.php?personID=I36809&tree=Herrmann. Thank you to Mark Bliese, Reference and Research Supervisor, for providing a biographical sketch on A.D. Greif.

[2] Obituary of Rev. Henry Proehl, New York Times (New York City, NY), Dec. 22, 1964, web, accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/12/22/archives/rev-henry-proehl-lutherah-teacher.html.

[3] Jacob [Aall Ottesen] Preus [II], “Martin Chemnitz’s approach to refuting error,” CSL Scholar, Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, November 5, 1986, audio recording, web, accessed September 28, 2022, https://scholar.csl.edu/sem/Recorded_Seminars/Year/16/.

[4] Martin Chemnitz, The Lord’s Prayer, ed. Georg Williams (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999).

[5] “Publications.” The Lutheran Heritage Foundation. Web. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://pubsearch.lhfmissions.org/

[6] Heinrich Schmid, Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, trans. Charles A. Hay and Henry E. Jacobs, (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1961), 665–666.