The Leap Day Lutheran:

Patrick Hamilton, Martyr

An online exhibit presented by Concordia Historical Institute

February 29, 2024

Introduction

Patrick Hamilton was the first Scottish Lutheran martyr—though you probably have never heard of him.

Many American Lutherans today have German heritage—perhaps going all the way back to the immigrants who fled Germany with C. F. W. Walther. However, as Lutheranism grew in America, more non-Germans and non-German speakers joined Lutheran churches. We see this heritage in the LCMS English District, which was originally a separate synod of English-speaking Lutherans. Because of the preponderance of Germans in our history, the historic touchstones linking the Lutheran faith with the English-speaking world are easy to overlook.

That’s why Concordia Historical Institute would like to present to you the story of the martyr Patrick Hamilton. Hamilton was a Scotsman who became Lutheran and was killed for his faith. His saint day—the anniversary of his death— is Leap Day, which means that it only appears on the calendar every four years. 2024 is a leap year, and the penultimate leap year before the 500th anniversary of Hamilton’s martyrdom (2028).

Our Lutheran churches look very different today than they did in the 1880s. Many LCMS Lutherans today do not trace their family history through the Saxon German immigrants—and many Lutherans during the Reformation were not German. Patrick Hamilton is once such instance, a reminder that Lutheranism didn’t “go English” in the 20th century with the Missouri Synod’s adoption of the English language. Patrick Hamilton is as much a part of our inspiring treasury of Lutheran history as Martin Luther. His writings and example are invaluable to us as English-speakers, as well as those of us with family ties to Scotland and the British Isles.

Life

Origins

Patrick Hamilton was born in the year 1504 in the area around Glasgow, Scotland. He was the great-grandson of King James II of Scotland, and his father, Sir Patrick Hamilton, was a knight. Thus, growing up in the society of men of power, wealth, and rank, Patrick himself would grow to have a reputation for courtesy, gentility, and virtue.

Education and Early Life

In 1517—the year Luther was nailing his theses to the church door in Wittenberg—the thirteen-year-old Patrick Hamilton became commendatory abbot of Fearn Abbey, Ross-shire. (A commendatory abbot was a temporary or “vacancy” abbot with minimal ecclesiastical privileges. He managed the administrative affairs of a vacant abbey or an abbey temporarily without an abbot. It is unclear—but unlikely—that Hamilton ever took monastic vows or presented himself as a monk.) At age fourteen, using the income from his position as abbot, Patrick went to study abroad in Paris at the Collège de Montaigu, earning his Master of Arts in 1520 at only sixteen years old! It was during this time, it seems, that Patrick first encountered the writings of Martin Luther.

University of St. Andrews

Luther’s 95 Theses and his other writings and disputations spread like wildfire around Europe. By 1519, Luther appears to have been well-known in the Collège. However, on April 15, 1521, the university decreed that Luther was a heretic and his works should be burned. (Philip Melanchthon himself would later write “A Defense of Martin Luther against the Furibund Decree of the Parisian Theologasters”—quite a punchy title, especially from the generally-sedate Melanchthon.)

From Paris, Hamilton then went to Louvain, Holland, to study under Erasmus at the university. He would later return to his native Scotland, to the University of St. Andrews, becoming a faculty member in 1524. While there, he also composed a mass for nine voices in honor of the angels, which he conducted at the university cathedral.

Reformation Rumblings in Scotland

In 1524, the year Patrick turned 20 years old, Luther’s works and Tyndale’s English New Testament began circulating throughout Scotland. Under the 14-year-old King James V, the Scottish parliament passed a law decreeing that anyone caught smuggling Luther’s works into Scotland would be subject to imprisonment and confiscation of property. Later, additional provisions stipulated all Lutherans (whether foreigners or Scotsmen) were subject to confiscation of their goods.

Although Lutheranism was spreading in Scotland, there was no Lutheran preaching. That is, until Patrick Hamilton became Lutheran.

Patrick Hamilton Becomes Lutheran

The only known portrait of Patrick Hamilton. (Artist: John Scougal, c. 1645-1730.)

Hamilton began publicly confessing his Lutheran leanings as early as 1526. He did not meet with approval or encouragement. Rather, his Archbishop, James Beaton, interrogated him and recommended a public trial—and the possibility of being burned at the stake.

As a result, Patrick fled to Germany in April 1527. Hamilton came to Wittenberg, soaking in everything the German Reformation had to offer. Luther had recently married the former nun, Katharina von Bora, and was living with her—now pregnant with their second child—in the Black Cloister. In Luther’s Wittenberg there was rich congregational singing, Gospel preaching, and communion in both kinds (bread and wine, the latter of which Roman Catholic churches withheld from the laity).

Hamilton left Wittenberg because of a bubonic plague outbreak, choosing to continue his studies in Marburg. While there, he met John Frith and William Tyndale, English theologians who would also end as martyrs for their reform-minded teachings. Patrick studied under Francis Lambert, a French monk who became Lutheran. Lambert said the following of Patrick:

“[Patrick Hamilton’s] learning was of no common kind for his years, and his judgment in divine truth was eminently clear and solid. His object in visiting the University [of Marburg] was to confirm himself more abundantly in the truth; and I can truly say that I have seldom met with any one who conversed on the Word of God with greater spirituality and earnestness of feeling.” [1]

Hamilton’s Theses

The first page in a Dutch edition of Patrick’s Places.

While at Marburg, Patrick Hamilton produced Lutheran theological theses for public debate. The dating of this work is unclear, but it was in circulation—including in his native Scotland—by 1528. These theses were in Latin originally, but the English Protestant (and later martyr) John Frith translated them into English as Patrick’s Places. This is because it is a theological Loci Communes or book of commonplaces.

Commonplace books were ways of organizing quotations from other sources. You can make a commonplace book with any type of source material—for example, many famous authors have used commonplace books to manage their favorite and most inspiring quotations from other works—but theologians in the Early Modern period especially liked the format. Philip Melanchthon’s Loci Communes is perhaps the best and most famous example of a Lutheran theological commonplace book, though others exist.

You can read an online edition of Patrick’s Places with modernized spelling here. (A transcribed version of the original text—including archaic spellings and formatting, is available from Oxford University’s Bodleian Library here.)

Much of Patrick’s Places will seem familiar and ring true to a Lutheran audience. Here is a brief selection, taken from the modernized edition linked above:

The Law saith,

Pay thy debt.

Thou art a sinner desperate.

And thou shalt die.

The Gospel saith,

Christ hath paid it.

Thy sins are forgiven thee.

Be of good comfort, thou shalt be saved.The Law saith,

Make amends for thy sin.

The Father of Heaven is wrath with thee.

Where is thy righteousness, goodness, and satisfaction?

Thou art bound and obliged unto me, to the devil, and to hell.The Gospel saith,

Christ hath made it for thee.

Christ hath pacified him with his blood.

Christ is thy righteousness, thy goodness, and satisfaction.

Christ hath delivered thee from them all.

Having spent six months in Germany, Hamilton was ready to return to Scotland, now fully convinced of the necessity of church reform. His friends back home pleaded with him to stay away for fear of death. But the threat of martyrdom could not keep Patrick away.

Return to Scotland and Marriage

Cardinal David Beaton, archbishop of Scotland.

In autumn 1527, Patrick Hamilton returned to Scotland. He preached the reformation tenants he’d learned in Germany to his friends and family around Kincavel and Linlithgow—drawing the ire of the monks nearby. Hamilton also, apparently following in Luther’s footsteps, married. His wife’s name is unrecorded, but she was a woman of minor nobility. They had one daughter named Isobel.

His open preaching and teaching of Lutheran doctrines soon attracted the eye (and ire) of the authorities. In January 1528, Cardinal David Beaton, Archbishop of Scotland, summoned Hamilton to appear in St. Andrews for private interviews. Hamilton saw the writing on the wall: He would soon be tried as a heretic.

Yet, for a month, the authorities allowed Patrick to teach and speak openly his Lutheran views at the university, which he did with boldness. In fact, he debated several Roman Catholic clergy, including Patrick’s friend, a Dominican friar named Alexander Campbell. Some of these Catholic clergy found him persuasive and agreed with his points. As a warm and affable young man with noble connections and notable intelligence, he was in the perfect position to share the hopes of the early Lutherans for a reformed church and purely-preached Gospel with the Scottish, and he did so until his tragically early death.

Trial and Death

A council of clergy headed by Cardinal Beaton called Patrick Hamilton to appear for a trial. Hamilton’s friends begged him to flee, but he refused. His own brother—a well-connected nobleman with substantial military forces at his disposal—attempted to arrange for a rescue force of sorts, however storming weather derailed this plan. Another noble, John Andrew Duncan, Laird (a rank below a baron and above a gentleman in Scotland) of Airdie, armed his tenants and servants in order to defend his friend from martyrdom. However, Duncan was arrested and forced into exile as a result of his actions. Patrick went to his trial and martyrdom undefended.

The Trial

The council of bishops and clergy, headed by Cardinal Beaton, accused Patrick of heresy. Patrick’s friend Friar Campbell betrayed Hamilton, bringing these thirteen charges to the Cardinal. They are as follows:

- That the corruption of sin remains in the child after baptism

- That no man is able by mere force of free will to do any good thing

- That no one continues without sins so long as he is in this life

- That every true Christian must know if he is in the state of grace

- That a man is not justified by works but by faith alone

- That good works do not make a good man, but that a good man makes good works

- That faith, hope, and charity are so closely united that he who has one of these virtues has also the others

- That it may be held that God is cause of sin in this sense, that when he withholds his grace from a man, the latter cannot but sin

- That it is a devilish doctrine to teach that remission of sins can be obtained by means of certain penances

- That auricular confession is not necessary to salvation

- That there is no purgatory

- That the holy patriarchs were in heaven before the passion of Jesus Christ

- That a priest has just as much power a pope [2]

Hamilton expressed willingness to discuss the last five statements further, however he declared he was firm on the first eight accusations. The council found him guilty of heresy, namely, “disputing, holding, and maintaining divers heresies of Martin Luther and his followers.” [3]

Martyr Patrick Hamilton’s Last Confession of Faith

Cobblestones in the form of the initials “PH” for Patrick Hamilton at St. Andrew’s University. A nearby historic marker reads: “The initials on the pavement nearby mark the spot where Patrick Hamilton, member of the university, was burned at the stake on 29 February 1528, at the age of 24. On the continent he was greatly influenced by Martin Luther, and on his return to St. Andrew’s he began to teach Lutheran doctrines. Having been tried and found guilty of heresy, he was condemned to death, thus becoming the first martyr of the Scottish Reformation.”

Guards escorted Hamilton first to his cell in the prison and then to the site of his execution, in front of the gate of St. Salvator’s College in the University of St. Andrews. A stake and wood for burning were ready. Patrick approached the place with a copy of the Gospels, which he gave to a friend, handing his faculty cap and gown to his servant. When asked if he would recant, Patrick responded:

“As to my confession, I will not deny it for awe of your fire, for my confession and belief is in Christ Jesus. Therefore I will not deny it; and I will rather be content that my body burn in this fire for confession of my faith in Christ than my soul should burn in the fire of hell for denying the same.” [4]

Patrick prayed, and then his executioners led him to the site of his martyrdom.

Patrick Hamilton, Martyr

The executioners bound Hamilton with an iron chain to a stake and lit a fire beneath him. Throughout the execution, Patrick spoke “divers comfortable speeches to the bystanders,” speaking encouragement to his followers. He also responded to the taunts of the friars in attendance, including his betrayer, Friar Campbell, who had brought charges against Hamilton. “Wicked man!” Hamilton cried. “Thou knowest it is the truth of God for which I now suffer. So much thou didst confess to me in private, and thereupon I appeal thee to answer before the judgment-seat of Christ.” He also commended his widowed mother into the care of his friends.

Someone in the crowd then stoked the flames with straw, which, combined with a sudden gust of wind, blew a pillar of flame directly toward Friar Campbell, Hamilton’s betrayer, burning off a significant portion of his monk’s cowl. (Campbell died soon after from a sudden illness, which was interpreted at the time as divine retribution.) Someone else in the crowd taunted Hamilton, asking if he still had faith in the doctrines for which he was being killed. Hamilton, on the brink of death, assented by raising his hand. His last audible words were, “How long, Lord, shall darkness overwhelm this kingdom? How long wilt Thou suffer this tyranny of men? Lord Jesus, receive my spirit!”

His execution latest nearly six hours. Patrick was only twenty-four years old. [5]

Remembering the Martyr Patrick Hamilton

Immediate Aftermath

When the Lutherans on the continent heard of Hamilton’s death, they grieved deeply. In Scotland, they considered Hamilton the forefather of the Scottish Reformation. His teacher Francis Lambert in Marburg was profoundly upset. He wrote that, if it would be God’s will, further Protestants would soon come to Scotland. He was right.

It is very curious that the Reformation in Scotland began not with the teachings of the English Wycliffe, nor the later Calvinist teachings that would become ascendant under John Knox, but with Luther. Luther’s books were still imported into Scotland after his death, and at least one Benedictine monk, Henry Forrest of Linlithgow, was moved to confess the same Reformation truths as Hamilton and declared Patrick a martyr. Henry Forrest was likewise martyred for his faith, as were other Scotsmen who found the freeing Gospel and the Bible in their own language because of Patrick Hamilton.

Patrick Hamilton and the Legacy of a Martyr

Patrick’s Places maintained relevance within Scottish protestantism. The Scottish John Knox and the English John Foxe both included the story of Patrick Hamilton’s martyrdom in their accounts of the Reformation in the British Isles. Despite the fact that Scotland did not undergo a “Lutheran Reformation,” but rather one that was heavily influenced by John Calvin’s doctrines, it is arguable that the early influence of Luther was substantial. Perhaps a future historian will be able to show us how the Lutheran element through Hamilton remained in Scottish Protestantism?

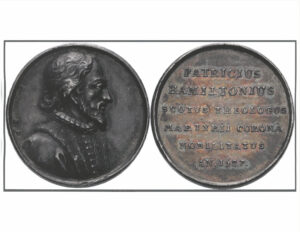

Obverse and reverse of Patrick Hamilton medal. From Daniel Harmelink, ed., The Reformation Coins and Medals Collection of Concordia Historical Institute: A Striking Witness to Martin Luther and the Reformation (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2016).

Another notable instance of Hamilton’s legacy is seen in the commemorative medal displayed to the right of this paragraph. There are few depictions of Hamilton at all—the only known painted portrait, one of only a very few artistic depictions of him at all, appears towards the beginning of this exhibit and also in the decorative exhibit title at the top of the page. But these kinds of commemorative coins and medals were very popular among Protestants in this period.

The bronze medal was designed by Genevan medallist Jean Dossier—at one point the official Mint Engraver for the Republic of Geneva—and struck c. 1720 as part of his series on Protestant reformers. The British Library has an example in its collection, which you can view online. The obverse (front) shows Patrick Hamilton in a side portrait, wearing a scholar’s fur robe. The reverse (back) bears a Latin inscription which reads in English:

Patrick Hamilton, a Scotsman, theologian, ennobled with the crown of martyrdom, 1527.

Patrick Hamilton, Martyr, and the LCMS

A Saint for English-Speaking Lutherans

The first mention of Patrick Hamilton in the LCMS is found in the work of William Dallman.

Charles Frederick William Dallman was born in Prussia on December 22, 1862. He immigrated to America as a child in 1868 and was educated at Concordia College, Ft. Wayne, and Concordia Seminary, St. Louis. He was ordained in 1886 and served in the English Synod in congregations in Missouri, Maryland, New York, and Wisconsin.

Dallman eventually became President of the English Synod from 1899–1901, then Vice President from 1901–1909. He helped transition the English Synod into the English District of the Missouri Synod, and served as a Vice President of the Missouri Synod from 1926–1932. Dallman also lived through the adoption of English as the language of worship and instruction in the LCMS, following the English Synod merger and in response to cultural shifts during World War I. Dallman also had a prolific career outside of the parish, serving as editor of the Lutheran Witness and the English Hymnal, as well as publishing a number of books and tracts. He retired to Oak Park, Illinois in 1940, where he later died on February 2, 1952.

Rev. Dallman was interested in the English-speaking Lutheran martyrs Robert Barnes and Patrick Hamilton. He wrote books on both, hoping to share the stories of these steadfast confessors of the faith with his fellow English-speaking Lutherans. This transition from German to English must have been hard for some in the Missouri Synod, and it must have also been challenging for non-Germans to feel at home in a tradition sometimes associated with a specific country and its culture. Dallman’s work to highlight Patrick Hamilton (and Robert Barnes) was surely helpful in reaching English-speaking Americans and showing that our Reformation faith is about more than German genealogy.

The Martyr Patrick Hamilton Today

More recently, LCMS pastor Rev. Jordan McKinley has produced a helpful biographical sketch of Hamilton, which we utilized in the creation of this exhibit. Rev. McKinley does not have German ancestry—as is increasingly the case with both laypeople and clergy in the LCMS. Discovering Patrick Hamilton was exciting to him because he has Scottish ancestry, proving that even during Luther’s own lifetime, the Lutheran faith wasn’t a German-only club.

Rev. McKinley also provided the introduction to a new edition of Patrick’s Places with additional helpful material, edited by fellow-LCMS pastor (emeritus) Rev. Don Matzat. Rev. Matzat remarks that, when we study the Reformation, as Lutherans, we tend to spend all our time on Germany. However, Matzat notes, though Luther and Melanchthon encountered grave threats, harsh treatment, and real challenges because of their faith, their government did not kill them for their faith. In fact, their prince sheltered them. England and Scotland, however, did kill their early Lutheran reformers. Nevertheless, the Reformation came to England, and it bore the marks of Luther’s teachings.

Rev. McKinley offers the following reflection on Hamilton’s testimony and martyrdom:

Patrick Hamilton is little remembered by modern Lutherans. The synopsis I’ve given here relies on tertiary sources that relied heavily on Peter Lorimer’s work. Although the Reformation in Scotland took a decidedly Calvinistic turn, the early work was done by bold Lutheran men like Hamilton. This is part of our proud heritage as Lutherans, regardless of our national identity. Praise God for such men, and would that He would grant us the same boldness of the martyrs who have gone before us. What I find particularly striking about Hamilton is that all this occurred before the Augsburg Confession was written (1530) or the Catechisms (1529). Though this bright Lutheran light was snuffed out in his day, let us let his light shine in the midst of our present darkness. [6]

Conclusion

There is still much scholarly work to be done in order to fully understand the life and honor the legacy of Patrick Hamilton. The recent interest in Hamilton has certainly increased his accessibility among English-speaking Lutherans, and perhaps future historians will unearth further sources and information on this man’s rich life and confession. Sadly, the Reformation in Scotland would go on to take a more Calvinist direction, eschewing the moderate reforms of the Lutherans for a more extreme approach. What would a Lutheran Scotland have looked like? What effects would this have had on the religious, social, and political context in the British Isles, and perhaps even broader European history? We’ll never know.

But today, now that Lutheranism is a viable and even thriving option for English-speakers—and truly, people of all languages, ethnicities, races, and places around the world—the testimony of Patrick Hamilton reminds us of Christ’s faithfulness to us in all times and places. Whether you are German, Scottish, both, or neither, ultimately, it is the faith of Patrick Hamilton and the message of Christ to which he so steadfastly clung that will continue to endure throughout the ages.

Notes

[1] Quoted in William Dallman, Patrick Hamilton (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1918), 16.

[2] Peter Lorimer, Patrick Hamilton, The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation (Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co., 1857), 143 accessed online February 15, 2024.

[3] Quoted in Dallman, Patrick Hamilton, 36.

[4] Lorimer, Patrick Hamilton, 152.

[5] Lorimer, Patrick Hamilton, 153–154; Dallman, Patrick Hamilton, 40–41.

[6] Jordan McKinley, “Sir Patrick Hamilton, The First Lutheran Martyr in Scotland,” in Steadfast Lutherans (February 29, 2016), accessed online February 15, 2024.

Learn more about Patrick Hamilton, Martyr

Primary Sources

Patrick Hamilton. Patrick’s Places. Translated by John Frith. 1526[?]. True Covenanter: n.d. Accessed online February 15, 2024.

Patrick Hamilton. [Patrike’s Places]. Translated by John Frith. Oxford Text Archive: 2011. Accessed online February 15, 2024.

Patrick Hamilton. Patrick’s Places: Patrick Hamilton’s Distinction between Law and Gospel, Faith and Works. 2019. See Amazon listing here.

Patrick Hamilton (commemorative medal). J. Dassier. 28mm diameter. 10.30g. Bronze. Struck c. 1720. Online exemplar.

Other Resources

Dallman, William. Patrick Hamilton. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1918. Available at Concordia Historical Institute and online at Archive.org.

Daniel Harmelink, ed. The Reformation Coins and Medals Collection of Concordia Historical Institute: A Striking Witness to Martin Luther and the Reformation. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2016.

“Fearn Abbey.” Wikipedia. Last updated February 10, 2024. Accessed February 15, 2024.

Lorimer, Peter. Patrick Hamilton, The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation. Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co., 1857. Accessed online February 15, 2024.

McKinley, Jordan. “Sir Patrick Hamilton, The First Lutheran Martyr in Scotland.” Steadfast Lutherans. February 29, 2016. Accessed online February 15, 2024.

“Commendatory Abbot.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. Accessed February 15, 2024.

“Patrick Hamilton (martyr).” Wikipedia. Last updated January 15, 2024. Accessed February 15, 2024.